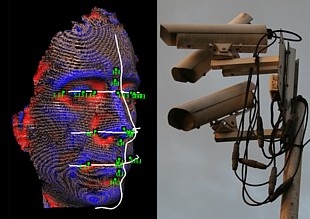

Senator Franken called the hearing out of concern for the speed at which facial recognition technology is progressing as its use remains unregulated. Dr. Alessandro Acquisti, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, said facial recognition could soon become a casual pursuit as computers get smaller, more powerful, and cloud computing costs come down. "Within a few years, real-time, automated, mass-scale facial recognition will be technologically feasible and economically efficient," Acquisti wrote in a statement; for companies, for friends, and for law enforcement.

Facial recognition has two characteristics that alarmed most members of the panel. First, faces (unlike other common information gatekeepers like passwords or PIN numbers) can't be changed for protection. Second, neither permission nor interaction is required for one person to capture the face of another. If they're in public, their visage is fair game. Facial recognition "creates acute privacy concerns that fingerprints do not" because of the ease of collection, Franken said.

But facial recognition itself is less of a concern than the supplementary data that drives it. Several panelists described scary and intrusive applications of facial recognition: a random person takes a photo of another and an app pulls up their address and the names of family and friends; a camera in a pharmacy recognizes your face and asks loudly whether you need more Imodium—and here's a dollar-off coupon toward your purchase. "It's the aggregation that frightens people," said Dr. Nita Farahany, a professor at the Duke University School of Law. "We don't stop the flow of information, or say certain applications are limited or permissible."

All parties at the hearing agreed that facial recognition can be used to both benefit and take advantage of consumers. But right now, there is little to prevent the advantage-taking. Data sharing settings put in place by aggregation companies have lately been coercive, positioned as take-it-or-leave it scenarios to consumers. Google, for instance, created a broad new privacy policy that gave it much more flexibility in how it collects and uses user data, where users' only way out was deleting their accounts. Facebook also changed its privacy policy in May, adding points like one that allows third-party apps to keep users' information even if the app had been deleted, unless explicitly asked to delete it.

While the hearing was heavy with concerns, solutions or suggestions for legislating facial recognition were not forthcoming. Should it be policed like wiretaps? Should its use be limited like medical information? Franken asked the Federal Trade Commission's representative, Maneesha Mithal, if she could compel the FTC to mandate that companies make facial imprint-related services an explicit opt-in service only. All Mithal could promise was that she would take the request back to her committee for further consideration.